Investigating the historic Luso-Asian connections in early colonial Brazil

- Club Lusitano

- Oct 21, 2025

- 5 min read

By Professor Clifford Pereira

The arrival of Pedro Álvarez Cabral at Porto Seguro in Brazil in 1500 ushered Portuguese colonisation in the Americas, and the beginning of a process of exploitation, removal and ultimately the extermination of many indigenous peoples. Today’s version of the history of Brazil stresses the European and African settlement often at the detriment of the original Brazilian ‘Indians”. The early Asian aspect in the history of Brazil is virtually unknown and confined to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Early colonial Brazil was divided into fifteen captaincies that extended from the coast to the longitudinal line established by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas which divided the world between Spain and Portugal. My field research in 2012 concentrated on the present Brazilian state of Bahia, which is composed of three old captaincies: Bahia, Ilhéus and Porto Seguro.

The Portuguese circulated their captains globally and in 1534 Francisco Pereira Coutinho who had been at the 1510 conquest of Goa was offered the captaincy of Bahia. Another Asia-hand, Tomé de Sousa arrived in Salvador with the first Jesuit missionaries as the first governor-general of Brazil in 1549.

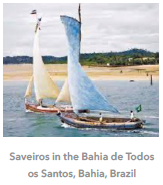

Tomé de Sousa established a shipyard and encouraged the repairs and victualing of returning Portuguese East India vessels. Due to a lack of Portuguese crew, the returning vessels were manned by Asian and African crewmen. The ship’s carpenter was an essential crewman and many of these were taken on in Asia. Asian influence was found in a type of boat used around the wide bay at Salvador. This boat called a Saviero is constructed with the use of measurements based on the palm of the hand and an instrument from India called a Graminho. Though the modern name is borrowed from a fishing vessel found in the Algrave and there are features of possible Dutch origin.

The Jesuit study of plants in Asia was transferred to Brazil and the Misericordia in Salvador still holds a collection of labelled drug containers called ‘mangas de farmácia’ for the major spices from Asia. These spices were initially used more for their medical properties then for enhancing food. When the first bishop Dom Pedro Fernandes Sardinha arrived in Salvador in 1522, he brought his attendants including those who had served him in Goa. The Brazilian Dominicans also included some who had served in Asia.

The major landlord of Santo Amaro and São Francisco on the outskirts of Salvador became part of the property of Fernando de Noronha, Third Count of Linhares who was the cousin of the Viceroy of India (which included Macau) between 1540 and 1608. At Santo Amaro is the small, cloistered convent of Praça Frei Bento whose small museum (Museu do Recolhimento dos Humildes) contains many religious items with Asian influences. The arrival of sugar cane production in the sixteenth century required the importation of millions of enslaved Africans. Abandoned sugar-mills and mission chapels dot the landscape of this area. By 1585 Brazil was the largest producer and exporter of sugar in the world, its capital of Salvador developed rapidly.

On the 5th May 1668 the Santissimo Sacramento sank of the coast of Salvador. Many objects from this wreck have been lost, but the remnants include cowrie shells (known as Zimbo’s or Buzia de Costa) from the Indian Ocean, ceramics imported through Macau with the coat of arms of the Silva family and nutmeg containers or Nozeras demonstrating the trade links with the Banda islands in present day Indonesia.

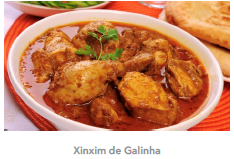

Luso-Asians are rarely mentioned in the early records, but we know that Asian women were in the retinue of the Portuguese captains who had served in Asia. As I dug into the intangible culture of Bahia, I found the cultivation of coconut trees and the use of coconut in the cuisine. Coconuts are not indigenous to the Atlantic, but were introduced from the Indian Ocean, and the use of coconut milk in Brazilian dishes such as prawn or fish Moqueca and Xinxim de Galinha are indicative of Asian influences and the presence of Asian women. The Xinxim in particular has ginger, garlic and onions as its base – a mixture often coined ‘the Indian culinary trinity’. It also uses Black Pepper and some versions use dried shrimp in the same way as some Macanese, Melakan and Goan curries do. Over time these recipes were cooked by enslaved West African women who brought their own influences in the form of peanut paste and palm oil or Dendê. Asian influences are also found in the Brazilian sweet Cocada and in the Mango preserve Mangada. In fact, the Mango was introduced from India. Another sweet with Asian influence is the steamed rice pudding known as Acaça.

In the seventeenth century the Viceroy of India was ordered to send two Goan cultivators of spice in Bahia and in 1682 the Jesuits succeeded in growing pepper and cinnamon in Brazil. Two further ex-Asia viceroys served in Brazil; Viceroy Pedro António Meneses de Noronha de Albuquerque served from 1714 and 1718 and Vasco Fernandes Cesar de Noronha de Albuquerque served from 1720 to 1735. The viceroys of India were called to send cultivators of coconuts, and married weavers of cotton. In 1763 Rio de Janeiro replaced Salvador as capital of Brazil.

On the 27th of November 1807, the Braganza royal family of Portugal, headed by Queen Maria I and Prince Regent João with the entire court of almost 10,000 people left Lisbon to escape the army of Napoleon for the city of Salvador in Bahia, Brazil. The court then set itself up in the city of Rio de Janeiro which became the capital of ‘The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves’ in 1815.

Though distant Macau or Goa don’t appear in this elaborate title, like the African colonies they were governed from Rio de Janeiro. The royal court eventually returned to Portugal in 1821. The period of Portuguese rule from Brazil is the period when uniquely, a European court experienced the colonial life of the tropics, including the climate, the social issues of slavery and the lack of nonagricultural industry. One of the interests of the royal court was the development of a Royal Botanical Garden, and no expense was spared. The court requested 300 Chinese tea planters in 1814 through agents in Macau. After the abolition of the slave trade and the rise of the coffee industry the independent Brazilian government sought new sources of labour and turned to Macau for the supply of Chinese labour. This resulted in foundation of the largest Chinese Brazilian community around Liberdade in São Paulo.

Early colonial Brazil was not the ‘diamond the Portuguese imperial crown’, that position was claimed by ‘the Indies’ – the sole sources of diamonds, exquisite porcelain, pepper, cloves, nutmeg and mace. It is hardly surprising that the Portuguese empire in Asia played a part in early colonial Brazil and left a legacy, even if this is now only visible in agriculture and cuisine.